Pianist and Louis Durey scholar Jocelyn Dueck’s recent art song recording, a collaboration with critically acclaimed vocalists Jesse Blumberg (baritone), William Burden (tenor), Sidney Outlaw (baritone), and Adriana Zabala (mezzo-soprano), shines deserved light on the vocal works by this underappreciated member of the Les Six group of composers.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Performer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 66:41 | |||

Six Madrigaux de Mallarmé |

||||

| William Burden, tenor, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 01 | Offert avec un verre d'eau | Offert avec un verre d'eau | 1:01 | |

| 02 | Jour de l'an | Jour de l'an | 0:55 | |

| 03 | Départ | Départ | 1:12 | |

| 04 | Eventail I | Eventail I | 0:47 | |

| 05 | 1er Avril 1887 | 1er Avril 1887 | 1:14 | |

| 06 | Eventail II | Eventail II | 1:11 | |

Deux Lieder Romantiques |

||||

| Sidney Outlaw, baritone, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 07 | Mon pâle visage | Mon pâle visage | 2:44 | |

| 08 | Tu es telle qu’une fleur | Tu es telle qu’une fleur | 1:05 | |

Trois poèmes de Paul Valéry |

||||

| Jesse Blumberg, baritone, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 09 | L’insinuant | L’insinuant | 2:01 | |

| 10 | Intérieur | Intérieur | 1:34 | |

| 11 | La Fausse morte | La Fausse morte | 2:13 | |

Deux poèmes d’Ho Chi Minh |

||||

| William Burden, tenor, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 12 | Je lis | Je lis | 1:34 | |

| 13 | Nuit d’automne | Nuit d’automne | 1:52 | |

Cantate de la rose et de l’amour |

||||

| Adriana Zabala, mezzo-soprano, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 14 | Introduction/Une rose a pris pour visage… | Introduction/Une rose a pris pour visage… | 1:40 | |

| 15 | Une rose n’est qu’une rose… | Une rose n’est qu’une rose… | 1:00 | |

| 16 | Une rose de crepuscule… | Une rose de crepuscule… | 1:02 | |

| 17 | Une rose qui s’émerveille… | Une rose qui s’émerveille… | 0:48 | |

| 18 | Une rose qui désespère… | Une rose qui désespère… | 1:40 | |

| 19 | Une rose à d’autres ressemble… | Une rose à d’autres ressemble… | 0:57 | |

| 20 | Une rose, cette innocence… | Une rose, cette innocence… | 0:54 | |

| 21 | Une rose, même d’automne… | Une rose, même d’automne… | 1:14 | |

| 22 | Une rose vient de me dire… | Une rose vient de me dire… | 0:59 | |

| 23 | Une rose toujours se cache… | Une rose toujours se cache… | 1:12 | |

| 24 | Une rose, cette étincelle… | Une rose, cette étincelle… | 0:56 | |

| 25 | Une rose rouge m’accable… | Une rose rouge m’accable… | 1:27 | |

| 26 | Une rose ne ressuscite… | Une rose ne ressuscite… | 1:00 | |

| 27 | Une rose: un coeur se divise… | Une rose: un coeur se divise… | 1:19 | |

| 28 | Une rose, ma confiance…/… Z. Coda | Une rose, ma confiance…/… Z. Coda | 1:39 | |

Quatre stances de Jean Moréas |

||||

| William Burden, tenor, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 29 | Belle lune d’argent | Belle lune d’argent | 1:35 | |

| 30 | Roses, en bracelet… | Roses, en bracelet… | 1:18 | |

| 31 | Quand reviendra l’automne | Quand reviendra l’automne | 1:45 | |

| 32 | Eau printanière | Eau printanière | 1:37 | |

| 33 | Grève de la Faim | Grève de la Faim | Jesse Blumberg, baritone, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | 5:31 |

| 34 | Une Femme du Sud Chante | Une Femme du Sud Chante | Sidney Outlaw, baritone, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | 3:12 |

Trois Poèmes de Paul Eluard |

||||

| Jesse Blumberg, baritone, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 35 | Bonne Justice | Bonne Justice | 1:55 | |

| 36 | Dit des Trieuses | Dit des Trieuses | 0:52 | |

| 37 | Des menaces à la victoire | Des menaces à la victoire | 5:16 | |

Quatre poèmes de Minuit |

||||

| Sidney Outlaw, baritone, Jocelyn Dueck, piano | ||||

| 38 | Ma haine | Ma haine | 1:22 | |

| 39 | Les deux lumières | Les deux lumières | 1:21 | |

| 40 | Malédiction | Malédiction | 2:19 | |

| 41 | Leurs noms bénis | Leurs noms bénis | 1:28 | |

IN 1917, French composers Louis Durey, Georges Auric, and Arthur Honegger formed the Nouveaux Jeunes under the aegis of Érik Satie which, in 1919, with the addition of Germaine Tailleferre, Francis Poulenc, and Darius Milhaud, became Les Six. Durey’s work has been relatively unexplored compared to his five colleagues.

Pianist and Durey scholar Jocelyn Dueck’s efforts have gone a long way towards righting that historical imbalance. Along with several critically acclaimed vocalists, she presents here this wonderful collection of recordings of several of succinct and rich art songs, in performances from unpremiered manuscripts.

Produced and Engineered by Adam Abeshouse

Edited, Mixed and Mastered by Adam Abeshouse

This recording was made possible in part by an award from

the Classical Recording Foundation

Special thanks to:

Anonymous, Joan Chiverton, Casie Dodge, Jeffrey Duban,

Ernest & Lorraine Dueck, Arlette Durey, Alain Durey, Even Dyrud,

Freyja Dyrud, The Field, Margo Garrett,

The David and Agatha Moll Charitable Fund, Katlyn Morahan,

Alexander Norelli, Fitz Patton, Ben Shirai, Dr. David Simpson,

Paul Sperry, and Pierre Vallet

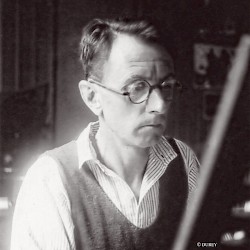

Photography: Arielle Doneson (Jesse Blumberg),

Simon Pauly (William Burden), Dan Wonderly (Jocelyn Dueck),

Hai Tran (Sidney Outlaw), Craig VanDerSchaegen (Adriana Zabala)

Design: Marc Wolf (marcjwolf.com)

Cover photo: Jeanette Hägglund

Translations from the French by Steven Jude Tietjen;

except Cantate de la rose et de l’amour, translation by Christopher Caines.

Texts and translations edited by Jocelyn Dueck and Christopher Caines.

Louis Durey was born in Paris on May 27, 1888, near the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés. After completing his secondary education, he earned a degree from the École des Hautes Études Commerciales (today better known as HEC Paris, one of the world’s leading business schools).

Louis Durey was born in Paris on May 27, 1888, near the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés. After completing his secondary education, he earned a degree from the École des Hautes Études Commerciales (today better known as HEC Paris, one of the world’s leading business schools).

It was not until he was about twenty years old, after discovering Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, that Durey determined to pursue a career in music. He began his studies in harmony, counterpoint, fugue, and composition as a private student—unaffiliated with any institution—of Léon Saint-Réquier, who was at the time a professor at the Schola Cantorum de Paris (an important private music school) and choirmaster at the Société des Chanteurs de Saint-Gervais.

Durey’s first compositions date from 1914 and testify to his deep affinity for the music of Debussy. In the same year, Durey encountered by chance one of the lieder from Arnold Schoenberg’s Book of the Hanging Gardens—a ray of light that opened the way for all of his later investigations. It was, more precisely, with Durey’s Offrande Lyrique, opus 4, that his own artistic personality emerged, as he delved into all the resources of his imagination—he was without doubt the first in France to make use of a musical language so clearly unconstrained.

In 1917, Durey, Georges Auric, and Arthur Honegger formed the Nouveaux Jeunes under the aegis of Érik Satie which, in 1919, with the addition of Germaine Tailleferre, Francis Poulenc, and Darius Milhaud, became Les Six. Durey “separated” from his comrades in Les Six in 1921, without however disrupting the bonds of honest friendship that had always united its members.

Durey was encouraged by several senior composers, including Albert Roussel, Florent Schmitt, and Charles Koechlin, and especially by Maurice Ravel, who among other things sponsored his membership in SACEM (the Société des Auteurs, Compositeurs et Éditeurs de Musique, the main French professional association that administers’ musical rights).

After spending the years 1921 to 1930 partly in the South of France, Durey settled once more in Paris, where he would remain until 1960, when he returned for good to Saint-Tropez.

Consulting the catalog of Durey’s works reveals that a great many of his compositions are devoted to vocal music, from solo art songs (mélodies) to vocal quartets accompanied by small instrumental ensembles. This form of expression predominated in his output between the wars and became, in a sense, his preferred field. It is evident that Durey always accorded the greatest importance to both his choice of poets and his choice of the specific texts he set, including poems by Apollinaire, Saint-John Perse, Cocteau, Mallarmé, Gide, Rilke, Éluard, and Lorca, among others.

In 1938 Durey, who was always particularly interested in the expressive forms of popular culture, was appointed general secretary of the Fédération Musicale Populaire, of which he became president in 1956, following in the footsteps of Roussel and Koechlin.

Beginning in 1944, Durey began to reveal openly in his music tendencies toward the expression of sentiments less personal than collective. His solo songs, choral works, and cantatas setting poems by such authors as Jean Fréville, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Éluard, and Langston Hughes exalt friendship, fraternity among the world’s peoples, and their ardent yearning for freedom and peace. At the same time, from 1943 to 1947, Durey undertook a number of musicological projects, including the reconstruction and editing of some one hundred songs in French by Clément Janequin, as well as various pieces by Guillaume Costeley, Lassus, and Luca Marenzio, and some of Josquin’s great motets—an activity that developed Durey’s appetite for choral writing. He also harmonized numerous French folk songs.

With his Six Pieces from Autumn ’53, opus 75, Durey returned to “pure” music, setting aside for a time the expression of ideas via the singing voice. Durey’s oeuvre, comprising 116 catalogued opus numbers, includes every major musical genre with the exception of scores for dance. He likewise created very little for the stage or the symphony orchestra, although he did compose music for several documentary films.

Durey also oversaw various collaborative venture in musical journalism from 1921 to 1930 (including Le Courrier Musical, The Musical News and Herald, The Chesterian), and published music criticism and reviews of recordings in such publications as Les Lettres Françaises, Europe, L’Art Musical Populaire, and La Nouvelle Critique.

Durey never allowed himself to be confined within any system, too jealous as he was of his complete expressive freedom. Always seeking ways to renew his work, he himself defined it as a continuity that took on a variety of guises: “I have always written what I felt like writing, according to my mood, my imagination, and my stubborness.”

While employing the most classical harmony, Durey also made use of atonalism and polytonality; in every case, the emotions to be expressed were the determining factor. Beyond the various aesthetic pathways he pursued, beyond any of his artistic influences, all of Durey’s music is suffused with his immense sensitivity, and his humanism.

– Translation Christopher Caines

Pianist Jocelyn Dueck is known for her new music interpretations on the New York City circuit, premiering and commissioning works by composers Eve Beglarian, Lisa Bielawa, Tom Cipullo, Corey Dargel, Matthew Schickele, Daniel Felsenfeld, Judd Greenstein, John Glover, Daron Hagen, Gabriel Kahane, Libby Larsen, Gilda Lyons, Robert Paterson, Kevin Puts and Gregory Spears, to name a few. Jocelyn was a collaborator on the Billboard Chart-topper Five Borough Songbook, as well as its newly released second volume in 2017. Jocelyn has served on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music, Juilliard, NYU and Mannes: The New School for Music, doing language preparation for their opera departments as well as teaching diction and duo interpretation classes. As a coach, Jocelyn has served on the music staffs at Glimmerglass Opera and Seattle Opera. Honors and awards include grants from the Classical Recording Foundation, Brooklyn Arts Council, Meet the Composer MetLife Creative Connections, American Composers Forum Encore, a Tanglewood Music Center Fellowship, and a Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade grant with her pianist sibling trio, Dueck Three for their concert tour of China. Jocelyn received a BA in Piano Performance and DMA in Accompanying and Coaching from the University of Minnesota. Her dissertation focused on the unpublished song cycles of Les Six composer Louis Durey. She is the leading expert on Durey’s songs in North America, having premiered the greater part of these cycles over the past decade. A devotee of language study through music, Jocelyn is the founder of The Center for Language in Song, an institute dedicated to the art of song performance.

Pianist Jocelyn Dueck is known for her new music interpretations on the New York City circuit, premiering and commissioning works by composers Eve Beglarian, Lisa Bielawa, Tom Cipullo, Corey Dargel, Matthew Schickele, Daniel Felsenfeld, Judd Greenstein, John Glover, Daron Hagen, Gabriel Kahane, Libby Larsen, Gilda Lyons, Robert Paterson, Kevin Puts and Gregory Spears, to name a few. Jocelyn was a collaborator on the Billboard Chart-topper Five Borough Songbook, as well as its newly released second volume in 2017. Jocelyn has served on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music, Juilliard, NYU and Mannes: The New School for Music, doing language preparation for their opera departments as well as teaching diction and duo interpretation classes. As a coach, Jocelyn has served on the music staffs at Glimmerglass Opera and Seattle Opera. Honors and awards include grants from the Classical Recording Foundation, Brooklyn Arts Council, Meet the Composer MetLife Creative Connections, American Composers Forum Encore, a Tanglewood Music Center Fellowship, and a Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade grant with her pianist sibling trio, Dueck Three for their concert tour of China. Jocelyn received a BA in Piano Performance and DMA in Accompanying and Coaching from the University of Minnesota. Her dissertation focused on the unpublished song cycles of Les Six composer Louis Durey. She is the leading expert on Durey’s songs in North America, having premiered the greater part of these cycles over the past decade. A devotee of language study through music, Jocelyn is the founder of The Center for Language in Song, an institute dedicated to the art of song performance.

American tenor William Burden has won an outstanding reputation in a wide-ranging repertoire throughout Europe and North America. He has appeared in many prestigious opera houses in the United States and Europe, including the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Los Angeles Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Seattle Opera, Opera Philadelphia, Santa Fe Opera, Cincinnati Opera, Glimmerglass Opera, New York City Opera, New Orleans Opera, Teatro alla Scala, Opéra National de Paris, Glyndebourne Opera Festival, Thèâtre du Châtelet, Bayerische Staatsoper, Berliner Staatsoper, Madrid’s Teatro Real, the Netherlands Opera, and the Saito Kinen Festival. A supporter of new works, he has created many roles, including V.P. Inglesias in Jimmy Lopez’ Bel Canto, Niklas Sprink in Kevin Puts’ Pulitzer Prize- winning Silent Night at the Minnesota Opera, and the role of George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life at the Houston Grand Opera. This season he returns to the Glimmerglass Festival for Derrick Wang’s Scalia/Ginsburg and as the 2017 Artist in Residence. Mr. Burden’s recordings include Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Barber’s Vanessa with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Musique adorable: The Songs of Emmanuel Chabrier. He also appeared in the Metropolitan Opera’s live HD broadcast of Thomas Adès’ The Tempest.

American tenor William Burden has won an outstanding reputation in a wide-ranging repertoire throughout Europe and North America. He has appeared in many prestigious opera houses in the United States and Europe, including the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Los Angeles Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Seattle Opera, Opera Philadelphia, Santa Fe Opera, Cincinnati Opera, Glimmerglass Opera, New York City Opera, New Orleans Opera, Teatro alla Scala, Opéra National de Paris, Glyndebourne Opera Festival, Thèâtre du Châtelet, Bayerische Staatsoper, Berliner Staatsoper, Madrid’s Teatro Real, the Netherlands Opera, and the Saito Kinen Festival. A supporter of new works, he has created many roles, including V.P. Inglesias in Jimmy Lopez’ Bel Canto, Niklas Sprink in Kevin Puts’ Pulitzer Prize- winning Silent Night at the Minnesota Opera, and the role of George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life at the Houston Grand Opera. This season he returns to the Glimmerglass Festival for Derrick Wang’s Scalia/Ginsburg and as the 2017 Artist in Residence. Mr. Burden’s recordings include Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Barber’s Vanessa with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Musique adorable: The Songs of Emmanuel Chabrier. He also appeared in the Metropolitan Opera’s live HD broadcast of Thomas Adès’ The Tempest.

Lauded by The New York Times as a “terrific singer” with a “deep, rich timbre” and the San Francisco Chronicle as an “opera powerhouse” with a “weighty and forthright” sound, Sidney Outlaw was the Grand Prize winner of the Concurso Internacional de Canto Montserrat Caballé in 2010 and continues to delight audiences in the U.S. and abroad with his rich and versatile baritone and engaging stage presence. This rising American baritone from Brevard, North Carolina recently added a GRAMMY nomination to his list of accomplishments for the Naxos Records recording of Darius Milhaud’s 1922 opera trilogy, L’Orestie d’Eschyle in which he sang the role of Apollo.Recent highlights for Mr. Outlaw include his Spoleto Festival debut as Jake in Porgy and Bess, Mercutio in Roméo et Juliette with Madison Opera, Vaughan Williams’ Dona nobis pacem with the Memphis Symphony Orchestra, recitals with Warren Jones, and a return to the New York Philharmonic and the Charlotte Symphony.

Lauded by The New York Times as a “terrific singer” with a “deep, rich timbre” and the San Francisco Chronicle as an “opera powerhouse” with a “weighty and forthright” sound, Sidney Outlaw was the Grand Prize winner of the Concurso Internacional de Canto Montserrat Caballé in 2010 and continues to delight audiences in the U.S. and abroad with his rich and versatile baritone and engaging stage presence. This rising American baritone from Brevard, North Carolina recently added a GRAMMY nomination to his list of accomplishments for the Naxos Records recording of Darius Milhaud’s 1922 opera trilogy, L’Orestie d’Eschyle in which he sang the role of Apollo.Recent highlights for Mr. Outlaw include his Spoleto Festival debut as Jake in Porgy and Bess, Mercutio in Roméo et Juliette with Madison Opera, Vaughan Williams’ Dona nobis pacem with the Memphis Symphony Orchestra, recitals with Warren Jones, and a return to the New York Philharmonic and the Charlotte Symphony.

Baritone Jesse Blumberg enjoys a busy schedule of opera, concerts, and recitals, performing repertoire from the Renaissance and Baroque to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He has performed roles at Minnesota Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, Atlanta Opera, Boston Early Music Festival, and London’s Royal Festival Hall. Jesse has made concert appearances with American Bach Soloists, Boston Baroque, Apollo’s Fire, and on Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series, and he has performed recitals with the New York Festival of Song, Marilyn Horne Foundation, and Mirror Visions Ensemble. He has been featured on over fifteen commercial recordings, including Schubert’s Winterreise with pianist Martin Katz and the 2015 Grammy-winning Charpentier Chamber Operas with Boston Early Music Festival. Jesse is also the founder and artistic director of Five Boroughs Music Festival in New York City.

Baritone Jesse Blumberg enjoys a busy schedule of opera, concerts, and recitals, performing repertoire from the Renaissance and Baroque to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He has performed roles at Minnesota Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, Atlanta Opera, Boston Early Music Festival, and London’s Royal Festival Hall. Jesse has made concert appearances with American Bach Soloists, Boston Baroque, Apollo’s Fire, and on Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series, and he has performed recitals with the New York Festival of Song, Marilyn Horne Foundation, and Mirror Visions Ensemble. He has been featured on over fifteen commercial recordings, including Schubert’s Winterreise with pianist Martin Katz and the 2015 Grammy-winning Charpentier Chamber Operas with Boston Early Music Festival. Jesse is also the founder and artistic director of Five Boroughs Music Festival in New York City.

http://www.jesseblumberg.com

Among the six world premiere roles she has created, mezzo- soprano Adriana Zabala sang the title role in Aldridge’s Sister Carrie, Sister James in Doubt, Lucy in Bolcom’s Dinner at Eight, and Manja in Steal a Pencil for Me. Recent seasons also included Martin Y Soler’s L’Albore di Diana, Viardot’s Le Dernier Sorcier at the Kennedy Center’s Millenium Stage, Catan’s Florencia en el Amazonas with San Diego and Madison Operas, and Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos with the Berkshire Opera Festival. In addition to several recordings and traditional operatic roles throughout the U.S., she has been a soloist with the Minnesota Orchestra, the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, the New Jersey, Jerusalem, Virginia, and Jacksonville Symphonies, and has appeared in recital at the Kennedy Center, Carnegie Hall, Wolf Trap, with the Source Song Festival, The New York Festival of Song, and the Salzburg Chamber Music Series.

Among the six world premiere roles she has created, mezzo- soprano Adriana Zabala sang the title role in Aldridge’s Sister Carrie, Sister James in Doubt, Lucy in Bolcom’s Dinner at Eight, and Manja in Steal a Pencil for Me. Recent seasons also included Martin Y Soler’s L’Albore di Diana, Viardot’s Le Dernier Sorcier at the Kennedy Center’s Millenium Stage, Catan’s Florencia en el Amazonas with San Diego and Madison Operas, and Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos with the Berkshire Opera Festival. In addition to several recordings and traditional operatic roles throughout the U.S., she has been a soloist with the Minnesota Orchestra, the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, the New Jersey, Jerusalem, Virginia, and Jacksonville Symphonies, and has appeared in recital at the Kennedy Center, Carnegie Hall, Wolf Trap, with the Source Song Festival, The New York Festival of Song, and the Salzburg Chamber Music Series.

Music journalist and composer Henri Collet dubbed Louis Durey, Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Germaine Tailleferre, Francis Poulenc and Darius Milhaud "Les Six". Of this half-dozen the name of Louis Durey is more likely to be the one you forget when someone challenges you on Counterpoint or Musical Trivia. Tailleferre has had more of a profile than Durey. It's good that pianist, professor, coach and music researcher Jocelyn Dueck has, in recent years, been at the forefront of Durey scholarship. She has now, through this art-song project, added invaluably to this composer's presence in the catalogue. Durey's family entrusted Dueck with this revival and with his vocal piano manuscripts of which she has a collection of sixteen cycles and stand-alone songs. We are told that Durey, on the one hand "spent time reconstructing French Renaissance music", but also composed many vocal pieces "engaged in the political climate of his era".

Durey's career spanned the twentieth century with concise, lyrical, tuneful, searching and provocative songs: a patrimony that enriches the wide field of French mélodie. These are far from long-winded: 41 songs in 67 minutes. The longest cycle (15 songs) here runs to short of 18 minutes. All are in the French language and the flow of compositions recorded on this CD began in the year after the Great War when the composer was 31 and ended in 1965, some 14 years before Durey's death.

The Six Madrigaux de Mallarmé start with a delicately cooing and lilting song (Offert avec un verre d'eau) rather like Poulenc but ends chaste and grim with Schoenbergian piano notes ringing out in stony defiance. Then come Deux Lieder Romantiques from the same year. It's a strange - and presumably carefully calculated - title that mixes the two languages. The second of the two, Tu es telle qu’une fleur, has a gently ringing piano part. The Trois Poèmes de Paul Valéry continue the tendency towards mournful beauty with a shade more defiant variety in La Fausse morte. I might have expected to see songs setting Ho Chi Minh in Alan Bush's catalogue. Durey's 1951 settings have both delicacy and resilience. The piano part illustrates, with a trace of sternness, the references to 'maps' and 'partisans'. Cantate de la rose et de l’amour is the latest piece here. These little lyrical gems for soprano run between 0.48 and 1:39. There is nothing here to test the listener's attention span. Some of them adopt the relaxed pastoral mood adopted by Milhaud in his first two symphonies, Suite Provençale and Chansons de Ronsard. It's remarkable that Durey was writing in this idiom in the mid-1960s.

Back to the tenor for Quatre stances de Jean Moréas with their pleading tone and idyllically rippling piano figuration. There are two isolated songs from 1950: the mistily despairing Grève de la Faim and Une Femme du Sud Chante. The latter has sections spoken in a simulation of the fatigue described by African-American poet Langston Hughes. His poetry was also set by Weill and Zemlinsky. The spoken segments lend the song a chill comparable with the whispered sinister magic to be found in Warlock's The Curlew. From three years later comes Trois Poèmes de Paul Éluard. Their mix of bitterness, sans-souci and what I take to be the phantoms of the German Occupation is nicely channelled by Jesse Blumberg. Spoken episodes are chillingly used in Des menaces à la victoire. A bleak and murderous wartime is sharply honed in the unrelieved Malédiction - the third song of Quatre poèmes de Minuit (1944). These songs carry a grim and tragic message until the final Leurs noms bénis with its shiver of sadness and chastening joy: "Tomorrow their blessed names will be / thousands of birds / Perched on the edge of bouquets for the dead."

With one blip the informative booklet exemplifies excellence, style, simplicity and clarity pari passu. The blip? That the libretto for the songs is not numbered at all so as you leaf through the texts you cannot easily relate what you are hearing to the disc-tracks. Otherwise very well done indeed, including the scene-setting essay. The sung French is printed with English translation opposite.

If you are looking to push the boat out further into Durey waters there is a piano music CD from Calliope with pianists Madeleine Chacun and Françoise Petit. This New Focus disc nicely dovetails with Hyperion's Louis Durey song collection from François Le Roux and Graham Johnson. It only "bumps" when it comes to two songs: Deux Lieder Romantiques appearing on both. The Le Roux survey concentrates exclusively on songs from the years 1918-19. Le Roux also tackled Durey's Basque songs with string quartet for the Swiss Gallo label.

The present well-recorded collection serves to transform Durey's presence from a niche to a deeper shelf.

Rob Barnett, 9.26.2017, Music Web International

This is titled “The Unpublished Song Manuscripts of Louis Durey (1888–1979)”. It offers 41 songs in 66 minutes. Most of the songs are thus quite short.

Durey was one of “Les Six”. He was ill at ease with their unofficial spokesman, Jean Cocteau, and separated from the group after a few years. Durey’s personality seems to have been somewhat retiring (except in his organizational work on behalf of living composers or political causes). He began studying music seriously at around age 20, mainly on his own and with one private teacher. He was fascinated with Debussy’s Pelleas and with Schoenberg’s freely atonal works (e.g., Book of the Hanging Gardens). Ravel encouraged him. Durey was a music critic. He was active in the French Resistance and, after World War II, in the French Communist Party. His political commitments are reflected in some works here: two of the songs have texts by Ho Chi Minh, another sets a translation of a poem by Langston Hughes denouncing racism and lynching, and the longest song is a protest speech by Turkish Communist poet Nazim Hikmet. (These political songs are from the years 1950–51.) We also hear early settings of two poems by Heine (in translation) and of laconic, sometimes puzzling verses by Valery and Mallarmé. The songs from the middle and end of his career use texts that are more straightforward: the political items plus settings of living poets Paul Eluard, Gabriel Audisio, and Louis Emié—and a somewhat earlier one, Jean Moreas.

Durey composed in spurts and went silent in between. He had little luck getting his works performed. He rarely composed for large forces (other than chorus), and only 8 of his 25 song cycles were published in his lifetime. Yet he took composing seriously: the musical style in the 41 songs heard here varies greatly, suggesting that part of his problem—and his strength—was a restless, exploratory nature.

Francois Le Roux and Graham Johnson made an entire disc of Durey songs that John Boyer admired (S/O 2002). Recordings of a few instrumental works by Durey are semi-hidden in our index—in collections. (A word-search for the composer’s name finds them all.)

We are grateful to pianist Jocelyn Dueck for bringing us this collection of unpublished songs. Nothing here was included by Le Roux and Johnson. Dueck has taught and coached at major music schools and opera houses. The early sets were the topic of her DMA thesis at the University of Minnesota.

The booklet essay offers a quick survey of Durey’s life and career but says nothing about the music; but the poems are here with translation.

Durey was, it seems, nearly obsessed with poetry. He tried to write music that would be appropriate but not distract the listener. Most of the songs are in a moderate tempo, which allows the singer to put the words across. The piano accompaniment often consists of slow-moving chords (the music is for the most part freely tonal, sometimes pandiatonic), pedal points, and gentle countermelodies. Sometimes the piano ripples engagingly in response to images of wind or water. And the songs of political and social protest can kick up quite a storm. A few times I was reminded of Samuel Barber, another song composer acutely responsive to poetry.

The performances are generally quite effective. Mezzo-soprano Adriana Zabala sings her one cycle (15 short songs) with great security. Of the two baritones, Jesse Blumberg sings and interprets well, with much expressive variety. Sidney Outlaw has weaker French (coeur, heart, sounds as if it were corps, body) and an obtrusive vibrato. Tenor William Burden, now in mid-career, preserves an upper register that is admirably clear and incisive, suggesting great depth of feeling. But his lower notes are marked by a slow vibrato and are sometimes not firmly on pitch.

Jocelyn Dueck supports, prompts, and responds with great acuity. She also doesn’t try to disguise the quirky sudden endings of many of the songs. (The many epigrammatic songs tend to have neither prelude nor postlude.) In a way, this refusal to create smooth, comforting endings seems to be a principle on the composer’s part. By avoiding musico-rhetorical flourishes, Durey reminds us that these are settings of poetry, not just occasions for a composer to do what pieces of music normally do. Durey’s output raises basic questions of why composers compose, why singers sing, why pianists play, and for whom. I will return to this often, to share in the spirit of restless exploration that Durey and the performers embody.

Excellent balance between solo voice and piano.

Ralph P Locke, 9.2017, © American Record Guide