Composer Steven Ricks' Assemblage Chamber features three chamber works that incorporate elements of the Baroque into Ricks' glitchy, collage oriented textures. An eclectic artist who is active in electronic music and free improvisation in addition to through-composed acoustic work, Ricks filters Baroque influences through his omnivorous style, responding at the end of the recording with an electronic reaction piece, a reckoning with incorporating older material from the vantage point of 2022. Assemblage Chamber features performances by counter)induction, the NOVA Chamber Music Players, Aubrey Woods, Alex Woods, and Jason Hardink.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Performer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 45:53 | |||

Heavy with Sonata |

||||

| Aubrey Woods, violin, Alex Woods, viola, Jason Hardink, harpsichord | ||||

| 01 | I. Plotting Our Next (Dance) Move | I. Plotting Our Next (Dance) Move | 1:44 | |

| 02 | II. Sarah’s Gigabit Broadband | II. Sarah’s Gigabit Broadband | 4:09 | |

| 03 | III. I’ll Amend the Current Trend | III. I’ll Amend the Current Trend | 5:30 | |

| 04 | Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri (1683–1727) | Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri (1683–1727) | counter)induction, Daniel Lippel, guitar/prepared guitar, Miranda Cuckson, violin, Jessica Meyer, viola, Caleb van der Swaagh, cello, Benjamin Fingland, bass clarinet | 14:18 |

Piece for Mixed Quartet |

||||

| NOVA Chamber Music Players, Gerald Elias, violin, Hasse Borup, violin, Walter Haman, cello, Jason Hardink, harpsichord | ||||

| 05 | I. Dance of Spheres | I. Dance of Spheres | 3:56 | |

| 06 | II. Baroque Assemblage | II. Baroque Assemblage | 3:54 | |

| 07 | Assemblage Chamber | Assemblage Chamber | Steven Ricks, electronics | 12:22 |

To view the musical Baroque as a kind of stone-tablet monument to intellect or dexterity is the first mistake. The seedbed of that musical epoch, along with its subsequent flowering, was sown with adventure, defiance, mannerism, improvisation, eclecticism, and spectacle--nothing mechanical or rule-bound about it, only the discipline required by exploration itself. The second mistake is to take "baroque" and attach a "neo-" to it, then ape seventeenth- or eighteenth-century style with a few token dissonances or syncopations to freshen it for the present. That practice, so abundant in the past decades, offers only the most vacant tribute to the real musical Baroque.

As if to remedy those mistakes comes this trilogy of recent works by Steven Ricks. They are about Baroque music or rather its ideological and technical fountainheads: the collision of opposing mannerisms as the seventeenth century opened; the fluctuations between musical dialogues and monologues; the exploration of multifarious textures; exaggeration and juxtaposition--all traits that evolved from the esoterica of the early Baroque into the dramatic montages of style and fashion in the High Baroque works of Bach and Handel. Ricks refracts all these notions through his own harmonic and rhythmic prisms, sometimes assembling shards like stained-glass windows. To suit the times, Ricks often proceeds along an almost surrealist path by borrowing techniques from cinema--replacing cadences with, say, the iris, the dissolve, the blackout--or from vernacular technological manipulations (read "channel surfing").

The most recent of the trilogy in this album, Heavy with Sonata, opens with a regal processional over a repeated dotted-note figure from which violin and viola unspool their lines like ribbons. The overt harmonic progressions provide a sense of foundation and sturdiness, while the wafting melodies offer operatic yearning, although interrupted by fleeting moments of psychological breakdown. The second movement, a harpsichord-driven moto perpetuo that cycles and recycles loops, depicts fierce incessance--a breathless mechanical carriage ride in which, after a few moments of gasps, continues till the carriage gradually comes apart. In the third movement, the harpsichord relinquishes its passagework in favor of a series of block-chord declamations, against which the other instruments knock and click as if in either applause or protest. This contest of wills is interrupted by stasis, spectral whistling, itself interrupted by the harpsichord playing overt quotations of eighteenth-century style, glimpses through peepholes into the Baroque itself. The ensemble then undertakes a game of competing trills, swelling and receding in layers, as the music suddenly resembles startled flocks of assorted birds. That apparent climax gives way to a coda that echoes the layout of the work's opening but substituting the harpsichord's processional gestures with almost industrially repetitive ostinati.

The oldest piece in this set--a 2011 quartet of two violins, cello, and harpsichord--maps out quite different terrain. The first of its two movements, "Dance of Spheres," opens with the harpsichord as protagonist and the other three instruments trying out various ways of responding to its outbursts. Their commentary grows increasingly verbose, interacting more and more with the harpsichord's figurations, until three-fourths of the way into the movement, all the instruments fully entangle in style and gesture. The result is a singleminded narrative in which one perceives one motivic idiom being, in effect, continuously conjugated and re-conjugated. The second movement, "Baroque Assemblage," opens Webernesque in texture, but diatonic in harmony. Shards of some shattered eighteenth-century model seem to be shuffled and repositioned. Throughout the work, though, each string instrument is given its own stuttering arioso, as if to assert that instrument's independence from the otherwise prevailing texture of the moment. What stands out most in the movement, though, is the quasi-fiddling ritornello of sixteenth-note runs presented by the whole ensemble, positioned at similar distances from the beginning and the end of the movement.

Straddling the backs of these earliest and latest works is the largest and most adventurous of the set: a single-movement chamber concerto for guitar with the tantalizing title of Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri (1683-1727). It opens with a kind of saunter to which assorted voices and attitudes gradually attach themselves. The bass clarinet--the odd man out in any Baroque evocation--begins as a "selective resonator," then asserts greater independence. But as the work unfolds, it becomes something between a catalogue and a kaleidoscope, enumerating and superimposing possible states of action--including some free improvisation by guitar and violin--then interrupting them with unexpected synchronicity. The effect is of a series of vortices, which suddenly dissipate when the guitar introduces an insistently repeated note that spreads almost virally to the other players. Thenceforth, from atonal soliloquies to flashes of gesture straight out of the eighteenth century, the music evokes the ways that genius might collapse into madness. We hear different rates of throbbing, from rapid clockwork to human pulse itself in various stages of exertion. Only in time does the guitar emerge as the real protagonist, though sometimes surrounded by swirls of allusions sounding like a fast-forward button had been repeatedly pressed on "history" itself. The eventual cadenza--a miniature fantasia for solo guitar--quickly surrenders to a final two minutes of muted noises--largely improvised--from all the instruments, muffled as though the music had been buried alive.

The final track, "Assemblage Chamber," is not so much a trope on the other pieces as a peeling back of the material world in which those musical objects existed. The spiritual, even hallucinatory, quality in which electronic music has always specialized is now brought to bear by Ricks on his acoustic works. Nouns ranging from "refraction" to "hall of mirrors" come to mind, although none adequately conveys what takes place in this technological shadow world of sound. Suffice it to say that the imaginary alcoves of time passage and anatomical exploration of timbre and texture make this a fitting, if divinely unsettling, coda to the album.

Perhaps the greatest theme of the musical Baroque was the idea of reinvention. As one of the most blatant and notorious "new music" movements in western history, the Baroque attempted to recreate the whole project of music itself: spade up polyphony and replant it with monody and then, as the era wore on, replant polyphony alongside other musical crops in a patchwork acreage of cantatas, oratorios, operas, and concerti. Just so, in these works Ricks has invoked more than anything else the spirit of reinvention that animated the source of his homages. In 1734, J. P. Rameau wrote that there was "no higher appeal" than the reconciliation of "reason and instinct." If there is a better characterization of Ricks's artistry, I haven't found it.

-- Michael Hicks, from the booklet liner notes

Deconstruction and fragmentation are core components of composer Steven Ricks’ work. On a previous New Focus Recordings release from 2015, Young American Inventions (FCR158), Ricks processed the detritus of the American aural landscape through his own modernist lens, designing glitchy electronic and ensemble textures, peppering them with quotes from disparate sources like Steely Dan, Steve Reich, and Milton Babbitt, and mixing them with shards of drum samples and automated call center style voices. On Assemblage Chamber, Ricks turns to the past, mining the juxtapositions, improvisatory spirit, and rich rhetorical framework of the Baroque. Ricks’ deconstructive impulse flowers and perhaps inverts itself in this context, extrapolating possibilities instead of picking them apart. With wit and a deft compositional hand, Ricks creates three ensemble works, two featuring the harpsichord, that use Baroque conventions as a springboard to reveal a prismatic version of its characteristic tropes. The album closes with the electronic title track, a piece that functions as a kind of reconciliation between Ricks’ journey into the musical past and an artistic voice more familiar to those who know his work.

The French overture style repeated dotted rhythms that open Heavy with Sonata are subtly subverted as soon the harmonic language begins to unfold. Ricks migrates towards chord voicings which, while still connected by contrapuntal voice leading, stretch beyond Bachian harmonic function to a lush, open harmonic world. The grandeur of the processional phrases is momentarily shattered by chromatic outbursts, interrupted by the chaos of contemporary harmonic possibilities. The second movement unfolds in moto perpetuo style, featuring repeated, uneven loops that allude to the developmental strategy of fortspinnung. The third movement, “I’ll Amend the Current Trend,” opens with a syncopated passage that cycles through triadic areas, almost as if to check the tuning of the keyboard, while the strings pluck and poke in the background, as if to imitate the harpsichord’s dry manner of sound production.

Piece for Mixed Quartet also features harpsichord with a string ensemble, but finds Ricks in a decidedly more methodical mode. “Dance of Spheres” places the harpsichord and ensemble in direct dialogue, with the strings offering a range of responsive material to a series of cubist reorganizations of a primary harmonic progression. The two groups become increasingly fused over the course of the movement before they begin to move as one integrated machine. “Baroque Assemblage” opens with hints of a broken phrase that we have not yet heard – Ricks reveals it momentarily, a Vivaldi-esque ritornello of sequential arpeggios. But the movement retreats to off-kilter, unsteady repetitive figures interrupted by brief soloistic gestures in each instrument. In contrast to Heavy with Sonata’s seamless stylistic transitions, Piece for Mixed Quartet utilizes Baroque allusions as one component of a collage of contrasting elements.

Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri also vacillates between overt references to the Baroque and organic, mechanistic textures. The element of improvisation opens up an additional parameter, referencing its importance in the music of the 18th century. An introduction explores irregular repetitions of rhythmic motives within the unusual instrumentation (guitar, bass clarinet, string trio). The guitar then improvises over an uneven pizzicato background figure, joined shortly by the violin, facilitating a structural transition. Two reflective guitar cadenzas alternate between harmonics and rolled chords, providing soliloquies that reflect on the trajectory of the piece. We hear shades of the syncopated material from “I’ll Amend the Current Trend” re-orchestrated to integrate the anachronistic guitar and bass clarinet, before a tongue in cheek quotation of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons takes aim at one of the Baroque’s sacred cows. A driving, intertwined final section slowly disintegrates into pops, plucks, and snaps, settling into a vamp for an improvised coda between prepared guitar and non-pitched sounds in the strings.

In the final track, Assemblage Chamber, Ricks returns to the soundworld of Young American Inventions to take stock and reconcile with his foray into older aesthetics. Snippets of material from the earlier pieces and improvised fragments are processed and interwoven inside an electronic web that meditates on the music that came before. In this way, the title track is a reflection on the album as a whole, but also a debrief on a repertoire and tradition that is constantly being reexamined and reconsidered. By recontextualizing his aesthetic time travels in the final track, Ricks reclaims something of the adventurous spirit of the Baroque itself that is no longer located in the musical materials of the period, reminding us that at one time, everything old was brand new.

– Dan Lippel

Tracks 1-3 recorded September 28, 2021, Madsen Recital Hall, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT

Recorded, mixed, and edited by Jeff Carter

Track 4 recorded June 18, 2019, Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, NY

Recorded, mixed, and edited by Ryan Streber

Daniel Lippel, Editing Producer

Tracks 5-6 recorded March 13, 2011, Libby Gardner Hall, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Recorded, mixed, and edited by Carlton Vickers

Track 7 created, mixed, and edited by Steven Ricks from loops and material taken from tracks 1 - 6, with additional material provided by Daniel Lippel and Jesse Mills

Additional mixing by Jeff Carter

All tracks mastered by Lurssen Mastering, March 2022

Liner notes by Michael Hicks

Aubrey Woods’ rise as a professional violinist vividly demonstrates the versatility that is the sine qua non for twenty-first century musicians. Her artistic leadership and excellence as concertmaster for Ballet West are consistently on display at the Capitol, Rose Wagner, and Eccles theatres in Salt Lake City. She frequently performs with the Utah Symphony Orchestra. She appeared for several years with the Orchestra at Temple Square in weekly worldwide broadcasts and on recordings with the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square and notable soloists, including Bryn Terfel and Renee Fleming. Aubrey is equally in demand as a studio recording artist for movies, television, and in backing tracks for many popular artists. Her performances as a chamber musician include appearances with NOVA, Intermezzo, the Park City Chamber Music Series and, on the Baroque violin, with New York Baroque Incorporated, the Sebastians, and Musica Angelica. She may often be heard in company with her husband, Alexander Woods, as the Woodmusick Duo. Aubrey holds the Master of Music degree from Brigham Young University where she teaches as an adjunct faculty member. On this recording, she plays a violin made by Enrico Marchetti (1884).

Alexander Woods is a “showstopping” (New York Times) violinist, baroque violinist, and violist, known for his “deft, sensitive” (New York Times) playing and his “beautiful tone” (Early Music America Magazine). He has performed with groups such as New York Baroque Incorporated (NYBI), the Helicon Foundation, the Sebastians, the Talea Ensemble, the Orchestra of St. Luke’s (New York), and the Utah Symphony. A dual Canadian/American citizen, Alex’s international career has led him to perform at the Mostly Mozart Festival, Lincoln Center Festival, Festival Pablo Casals, Darmstadt Institute, Festival Wien Modern, and many others. A prolific and critically acclaimed recording artist, Alex’s work may be heard on the MSR Clas- sics, Acis, Tzadik, Bridge, and Tantara record labels. His performances and recordings have been featured on stations such as BBC Radio 3 (United Kingdom) and WQXR (New York). He frequently collaborates with his wife, Ballet West Orchestra concertmaster Aubrey Woods as the Woodsmusick Duo, and with his father, Rex Woods, Professor of Piano Emeritus at the University of Arizona. Alex is a member of the faculty at Brigham Young University, a member of the faculty ensemble the Deseret String Quartet, as well as the founder and director of the BYU Baroque Ensemble, an early music chamber orchestra performing on original instruments created by the Violin Making School of America. Alex studied at Yale University, Manhattan School of Music, and the University of Arizona. When he is not performing or teaching, Alex loves being at home with his wife, Aubrey, and their four boys.

Jason Hardink is a fearless interpreter of large-scale piano works both modern and historical. His recent debut at Weill Recital Hall was lauded for its audacious programming and pianism demonstrating “abandon and remarkable clarity” and a “capacity for tenderness and grace” (Anthony Tommasini, New York Times). His repertoire includes Michael Hersch’s The Vanishing Pavilions, Olivier Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus, the Liszt Transcendental Etudes paired with the Boulez Notations, and Wolfgang Rihm’s Klavierstücke, all of which he performs from memory. Recent performances include his debut at the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music as soloist in the North American premiere of Gerald Barry’s Piano Concerto. Much sought after as a chamber musician, Mr. Hardink has collaborated in recital with violinists Augustin Hadelich, Nicola Benedetti, and Phillip Setzer. He is performing Messiaen’s Des Canyons aux étoiles . . . with the Utah Symphony and Music Director Thierry Fischer, a work they will record for the Hyperion label, as well as the world premieres of four new solo piano works commemorating the centenary of the Charles E. Ives Concord Sonata. Commissioned composers include Jason Eckardt, Anthony R. Green, Inés Thiebaut, and Steve Roens.

In its twenty years of virtuosic performances and daring programming, the composer/performer collective counter)induction has established itself as a force of excellence in contemporary music. Hailed by The New York Times for its “fiery ensemble virtuosity” and for its “first-rate performances” by The Washington Post, c)i has given critically-acclaimed performances at Miller Theatre, Merkin Concert Hall, the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, Music at the Anthology, and the George Washington University. Since emerging in 1998 from a series of collaborations between composers at the University of Pennsylvania and performers at the Juilliard School, counter)induction has premiered numerous pieces by both established and emerging American composers; including Eric Moe, Suzanne Sorkin, Ursula Mamlok, and Lee Hyla. c)i has also widely promoted the music of international composers including Jukka Tiensuu, Gilbert Amy, Dai Fujikura, Diego Tedesco, and Elena Mendoza. Since its inception, c)i’s mission has been straightforward: world-class performances of contemporary chamber music, without hype and without agenda other than a complete commitment to the most compelling music of our day.

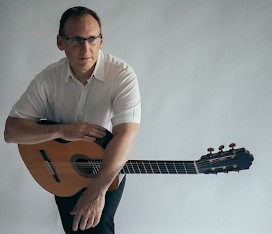

http://counterinduction.com/ Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Recently called “a fearless, visionary, and tremendously talented artist” (Sequenza21) and “a poetic soloist with a strong personality, yet unpretentious” (Die Presse, Vienna), Miranda Cuckson delights audiences with her playing of a great range of music and styles, from older eras to the newest creations. An internationally acclaimed soloist and collaborator, violinist and violist, she enjoys performing at venues large and small, from concert halls to casual spaces.

She has been a featured artist at the Berlin Philharmonie, Suntory Hall, Casa da Musica Porto, Teatro Colón, Cleveland Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, San Francisco’s Herbst Theater, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra’s Liquid Music, the 92nd St Y, National Sawdust, and the Ojai, Bard, Marlboro, Portland, Music Mountain, West Cork, Grafenegg, Wien Modern, Frequency, and LeGuessWho festivals. Miranda made her Carnegie Hall debut playing Piston’s Concerto No. 1 with the American Symphony Orchestra. She recently premiered Georg Friedrich Haas’ Violin Concerto No. 2 at the Vienna Musikverein and with orchestras in Japan, Portugal and Germany, and the Violin Concerto by Marcela Rodriguez with the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional de México. Miranda is a member of interdisciplinary collective AMOC and director of non-profit Nunc. She has guest curated at National Sawdust and programmed concerts at the Contempo series in Chicago and Miller Theatre in New York, among others. Her numerous lauded albums include Világ, featuring the Bartok Sonata for Solo Violin with contemporary works; the Ligeti, Korngold, Ponce, and Piston concertos; music by 20th century American composers; Bartók/Schnittke/Lutoslawski sonatas; Melting the Darkness, an album of microtonal/electronic music; and Nono’s La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura, named a Recording of the Year by The New York Times. An alumna of The Juilliard School, where she earned her doctorate, she teaches at Mannes College/New School University.

http://www.mirandacuckson.com/

With playing that is “fierce and lyrical” and works that are “other-worldly” (The Strad) and “evocative” (The New York Times), Jessica Meyer is an award-winning composer and violist whose passionate musicianship radiates accessibility and emotional clarity. Meyer’s compositions viscerally explore the wide palette of emotionally expressive colors available to each instrument while using traditional and extended techniques inspired by her varied experiences as a contemporary and period instrumentalist. Since embarking on her composition career at the age of 40, premieres have included performances by GRAMMY-winning vocal ensembles Roomful of Teeth and Vox Clamantis, the St. Lawrence String Quartet as the composer in residence at Spoleto Festival USA, the American Brass Quintet, PUBLIQuartet, Sybarite 5, NOVUS NY of Trinity Wall Street, a work for A Far Cry commissioned by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, the Juilliard School for a project with the Historical Performance Program, and by the Lorelei Ensemble for a song cycle that received the Dale Warland Singers Commission Award from Chorus America. She has also received multiple commissioning awards from both Chamber Music America and the New York State Council on the Arts.

Her first Symphonic Band piece was commissioned and toured by “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band (with a sold-out NY premiere in Carnegie Hall) and was a finalist for the William D. Revelli Composition Contest. Her orchestral works have been performed by the Phoenix, North Carolina, Charlotte, and Vermont Symphonies, the Nu Deco Ensemble in Miami, at Tanglewood in Seiji Ozawa Hall, and all around the country as part of Carnegie Hall’s nationwide Link Up Program. She was the winner of the 2nd Annual Ellis-Beauregard Foundation Composer’s Award to write a piece for the Bangor Symphony, and a winner of Chamber Music America’s Commissioning Program Award to write for the Argus Quartet. Recent premieres included works for the Dorian Wind Quintet, Hausmann Quartet, Hub New Music, the Portland Youth Philharmonic in collaboration with the female vocal ensemble In Mulieribus, and her viola concerto GAEA that she premiered alongside the Orchestra of the League of Composers at Miller Theatre in NYC. Upcoming premieres include works for the Bronx Arts Ensemble, the Brooklyn Art Song Society, the American Guild of Organists for their National 2024 Conference, and a new orchestral piece to be premiered by a consortium of orchestras across the United States. At home with many different styles of music, Jessica can regularly be seen as a soloist, premiering her chamber works, performing on Baroque viola, improvising with jazz musicians, or collaborating with other composer-performers. In 2023, she joined both the Viola and Chamber Music Faculty of the Manhattan School of Music.

https://jessicameyermusic.com A versatile chamber musician and soloist, cellist Caleb van der Swaagh is an alumnus of Ensemble ACJW (now known as Ensemble Connect) – a program of Carnegie Hall, The Juilliard School, and the Weill Music Institute in partnership with the New York City Department of Education. Caleb is a first prize winner in the SAVVY Chamber Competition and is the recipient of the Manhattan School of Music Pablo Casals Award and the Tanglewood Karl Zeise Memorial Cello Prize and was also a grant recipient from the Virtu Foundation. As a chamber musician, Caleb has performed with the Borromeo String Quartet, The Knights, A Far Cry, and the Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players and has recently appeared at such festivals as the Chelsea Music Festival, Ottawa ChamberFest, Garth Newel Music Center, Music from Montauk, and Birdfoot Festival. Caleb’s most recent release is the Carter Clarinet Quintet with Phoenix Ensemble on Navona and he has also appeared on recordings on Albany Records, Bright Shiny Things, Supertrain Records, Linn Records, and Avie Records.

A versatile chamber musician and soloist, cellist Caleb van der Swaagh is an alumnus of Ensemble ACJW (now known as Ensemble Connect) – a program of Carnegie Hall, The Juilliard School, and the Weill Music Institute in partnership with the New York City Department of Education. Caleb is a first prize winner in the SAVVY Chamber Competition and is the recipient of the Manhattan School of Music Pablo Casals Award and the Tanglewood Karl Zeise Memorial Cello Prize and was also a grant recipient from the Virtu Foundation. As a chamber musician, Caleb has performed with the Borromeo String Quartet, The Knights, A Far Cry, and the Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players and has recently appeared at such festivals as the Chelsea Music Festival, Ottawa ChamberFest, Garth Newel Music Center, Music from Montauk, and Birdfoot Festival. Caleb’s most recent release is the Carter Clarinet Quintet with Phoenix Ensemble on Navona and he has also appeared on recordings on Albany Records, Bright Shiny Things, Supertrain Records, Linn Records, and Avie Records.

An advocate of contemporary music, Caleb is a member of counter)induction and Ensemble Échappé as well as performing with other leading new music ensembles. Among many others, Caleb has premiered works by such composers as Beat Furrer, Ted Hearne, Iancu Dumitrescu, Christian Wolff, Roscoe Mitchell, and Georg Friedrich Haas. He also regularly performs his own compositions and arrangements.

A native New Yorker, Caleb graduated magna cum laude from Columbia University as part of the Columbia – Juilliard Exchange program with a degree in Classics and Medieval & Renaissance Studies. Caleb received his master’s degree with academic honors from New England Conservatory and later studied at the Manhattan School of Music. His primary teachers are Bonnie Hampton, Bernard Greenhouse, Laurence Lesser, and David Geber. Caleb plays on a cello made by David Wiebe in 2012. For more information, visit www.calebvanderswaagh.com

https://www.calebvanderswaagh.com/ Benjamin Fingland interprets a diverse range of clarinet literature, with performances conveying “spiritedness and humor”, “unflagging precision and energy”, "eloquence and passion", "dazzling technique" (The New York Times) and playing described as “something magical” (The Boston Globe), “compellingly musical” (The New York Times) and “thoroughly lyrical…expert” (The Philadelphia Inquirer). A proponent of the music of our time, he works closely with living composers. In addition to being a founding member of the critically-acclaimed new music collective counter)induction, he plays with many leading contemporary performance ensembles: NOVUS NY, the International Contemporary Ensemble, the New York New Music Ensemble, the Network for New Music, the Argento Ensemble, the Locrian Chamber Players, and Sequitur. He is a member of the renowned Dorian Wind Quintet, which will soon celebrate 60 years of groundbreaking commissions and performances of wind chamber music. He has Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from the Juilliard School and is on the faculty of the Third Street Music School Settlement in New York City.

Benjamin Fingland interprets a diverse range of clarinet literature, with performances conveying “spiritedness and humor”, “unflagging precision and energy”, "eloquence and passion", "dazzling technique" (The New York Times) and playing described as “something magical” (The Boston Globe), “compellingly musical” (The New York Times) and “thoroughly lyrical…expert” (The Philadelphia Inquirer). A proponent of the music of our time, he works closely with living composers. In addition to being a founding member of the critically-acclaimed new music collective counter)induction, he plays with many leading contemporary performance ensembles: NOVUS NY, the International Contemporary Ensemble, the New York New Music Ensemble, the Network for New Music, the Argento Ensemble, the Locrian Chamber Players, and Sequitur. He is a member of the renowned Dorian Wind Quintet, which will soon celebrate 60 years of groundbreaking commissions and performances of wind chamber music. He has Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from the Juilliard School and is on the faculty of the Third Street Music School Settlement in New York City.

Since its inception in 1977, NOVA Chamber Music Series has taken a leading role in the arts community of Utah, providing a venue for Utah artists and audiences to explore the vast chamber music repertoire. Founded by former Utah Symphony clarinetist Russell Harlow, NOVA's first decade featured many esteemed local musicians including violist William Primrose, Utah Symphony concertmasters William Preucil and Andrés Cárdenes, and numerous collaborations with composer Ramiro Cortés. NOVA’s first commission was the Cortés Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano in 1981. In 2009, Utah Symphony Pianist Jason Hardink was appointed Artistic Director. Under his leadership, the series deepened relationships with Utah composers while broadening NOVA’s profile nationally through commissions and recordings of works by composers Curtis Curtis-Smith, Jason Eckardt, and Michael Ellison. Over the following decade, NOVA would feature collaborations with Utah Symphony Music Director Thierry Fischer, soprano Celena Shafer, and the PLAN-B Theatre Company. The NOVA Gallery Series, performed in the intimacy of local art galleries and expanding NOVA’s presence to new neighborhoods in Salt Lake City and Park City, was added to NOVA’s schedule in 2013. As future Music Directors bring their own unique perspectives and experience to the NOVA Chamber Music Series in the coming years, audiences and the community are sure to benefit from an even broader and more diverse range of music.

Gerald Elias is a former violinist with the Boston Symphony and associate concertmaster of the Utah Symphony. He was a long-time faculty member of the University of Utah School of Music and first violinist of the Abramyan String Quartet. Elias has been music director of the Vivaldi by Candlelight chamber music series in Salt Lake City since 2004. In addition, he is the author of the critically acclaimed Daniel Jacobus mystery series and many other books and short stories.

Hasse Borup is Professor of violin and Head of String and Chamber Music Studies at the University of Utah School of Music. He has earned degrees in violin performance from the Royal Danish Conservatory of Music, the Hartt School of Music, and a Doctor of Musical Arts Degree from the University of Maryland. Dr. Borup has released recordings on Centaur, Naxos and Innova Labels: complete works for violin by Vincent Persichetti (Naxos 8.559725), the complete sonatas by the Danish romantic composer Niels W. Gade (Naxos 8.570524), and American Fantasies (Centaur 2918) both to critical acclaim (“Interpretative Empathy and Watertight Ensemble” —The Strad; “Landmark CD” – Musicweb; “Seamless playing” – allmusic.com). Tower of the Eight Winds, a CD on the Innova Label, featuring the complete works for violin by American composer Judith Shatin, was described by Fanfare Magazine as “ . . . being played with superb agility by the Borup/Ernst Duo.” Solo appearances include Vienna, Beijing, Washington DC, Venice, Cremona, Paris, Copenhagen and Miami. He was a founding member of the award-winning Coolidge Quartet, serving as the first ever Guarneri-Fellowship Quartet at University of Maryland. From 2005–09, Dr. Borup directed the Chamber Music Institute at the Music@Menlo Festival in California and has, since 2009, directed the University of Utah Chamber Music Workshop.

Walter Haman is a member of the Utah Symphony and Principal Cellist of the Grant Park Orchestra. He has also played with the Chicago, Honolulu, and San Francisco Symphony Orchestras. Mr. Haman is a member of Montage Music Society in Santa Fe and regularly performs on the Intermezzo and NOVA chamber music series in Salt Lake City. He is on the faculty of Utah State University.

Steven Ricks (b. 1969) is described in BBC Music Magazine as a composer “unafraid to tackle big themes.” He creates work that is bold, innovative, ambitious, and diverse, and that often includes strong narrative and theatrical influences. His music is performed and recorded by several leading art- ists and ensembles, including counter)induction (NY), New York New Music Ensemble, Canyonlands New Music Ensemble (SLC), Talujon Percussion (NY), Hexnut (Amsterdam, NE), Links Ensemble (Paris, FR), Manhattan String Quartet, Earplay (SF), NOVA Chamber Music Series (SLC), Empyrean Ensem- ble (SF), NY Metropolitan Opera soprano Jennifer Welch-Babidge, pianist Keith Kirchoff, guitarist Dan Lippel, flutist Carlton Vickers, and violinist Curtis Macomber.

Ricks has received commissions and awards from the Fromm Music Foundation, the Barlow Endowment, SCI, and Center for Latter-day Saint Arts, among others, and his music has been featured at multiple national and international conferences, festivals, and symposia, including ICMC, SEAMUS, NYCEMF, ISIM, KISS (Kyma International Sound Symposium), Third Practice, Festival of New American Music, and TRANSIT (Leuven, BE). Recordings of his music appear on multiple labels, including New Focus Recordings, Bridge Records, Albany Records, pfMENTUM, Vox Novus, and Comprovise Records. Ricks received degrees in music composition from Brigham Young University (BM), the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (MM), the University of Utah (PhD), and a Certificate in Advanced Musical Studies (CAMS) from King's College London. He is a professor in the BYU School of Music where he teaches music theory and composition and is the Music Composition and Theory Division Coordinator (2016 to the present). He is former Editor of the Newsletter for the Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States (2012–19), and was director of the BYU Electronic Music Studio for 20 years (2001–2021).

http://www.stevericks.comThere is much, ever so much New Music still, and the day we take it for granted is the day we must renew our love of being here with the music in the present-tense.. So, good readers, I come to you today with a kind of bubbling under excitement of a new disk of chamber works by Steven Ricks, in an album named after one of the compositions, Assemblage Chamber (New Focus FCR328).

There are Baroque elements, both musically and in instrumentation, at times and the overall impression I get is of a highly singular Neo-Classical Modernism of today. Liners author Michael Hicks instructs us to remember the Baroque as channeled by Ricks not "as a kind of stone-tablet monument to the intellect or dexterity," but rather something "sown with adventure, defiance, mannerism, improvisation, eclecticism and spectacle." The second cautionary assertion is not to "Take 'baroque" and attach a 'neo-' to it" which to Hicks entails imitating "seventeenth or eighteenth century style with a few token dissonances or syncopations" to make it Modern. Well that of course is not to be desired, but what does that have to do with the prefix "neo-," except perhaps as abused in the must facile of Neo attempts? If so, I agree. But then I might wonder, does Stravinsky qualify as Neo-Classical in some of his middle period music? And is it not completely and utterly Stravinsky-esque? Of course. And Hicks is right to caution us away from some mechanical vision of the period as it speaks to us, and truly Steven Ricks gives us nothing at all mechanical here, instead a living, breathing New Music that draws inspiration from the past but then transforms it into his own compositional matrix, just as he does the "Modernist" element as he claims it as his own.

There is nothing borrowed in this music as much as it is explored in transformation. And if "neo" still means "new" then Neo-Classical would only mean New Music in a Classical mode, which may then refer to elements of earluer periods incorporated but not necessarily to imply a servile copyist's vision, for surely Steven Ricks is a visionary as much as anything! I actually agree with Hicks, just not his abandonment of "neo" as a descriptor. But of course what matters is the music. And that is something to appreciate for sure.

So for example the Reconstructing the Lost Impressions of Aldo Pilestri (1683-1727) from 2018 includes transformed quotations from Vivaldi's "Seasons" but a great deal more elsewise to the naked ear, nicely scored for prepared guitar, violin, viola, cello, and bass clarinet. The end-experience of the music is simultaneously appropriation-transformation of the earlier musical world yet also completely immersed in the this-world of Modernity.

Heavy with Sonata (2021) takes the violin, viola and harpsichord medium and parallels the Baroque chamber sonata as rejuvenated and re-created to Ricks' own vision of musical unfolding.

The remaining Piece of Mixed Quartet (2011) and the electroacoustic cut and reassembled, ravishing Assemblage Chamber (2022) have more of the patented Ricks original novel appropriations and re-placements that are so striking in all of these works.

In the end this is some of the most original and inspired contemporary chamber music I have heard in years! The performances are right on it and the music gets better with every hearing. Hail Steven Ricks. Very recommended.

— Grego Applegate Edwards, 7.19.2022

Rather than questing into the future, Ricks bravely spelunks into the Baroque, pulling out modes and methods (and the occasional harpsichord, played by Jason Hardink) to inform his own bricolage approach. This gives the three acoustic pieces here a wonderful off-kilter feeling as past and present collide in lighthearted and inventive ways. The addition of guitar (Dan Lippel) and bass clarinet (Benjamin Fingland) creates ever more delightful anachronisms in Reconstructing The Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri, while the title track eliminates instruments altogether, with Ricks cutting and pasting bits and pieces of the earlier works into a sound collage that both sums everything up and points in new directions. With great playing by members of Counter)Induction and the NOVA Chamber Music Players, among others, this is a satisfying feast of a collection suitable for gourmands of many genres.

— Jeremy Shatan, 8.14.2022

Steven Ricks is a USAmerican composer and electronic musician crossing the borders between 'electronics' (read: beats), free improvisation, and contemporary classics. Unfortunately, Discogs (again, I think I have to get to work here ...) renders little to nothing about his recorded work (may even have split him into two persons). Nevertheless, what is delivered here, is accomplished work that manages to integrate musical history across several centuries.

Ricks is drawn to keyboards, and in the four pieces, two three- and two-movement ensemble pieces and two single tracks, he uses the harpsichord as 'his' instrument, contrasting keyboard lines with a string ensemble (in this case, the ensemble counter)induction), or in the single track, guitar and clarinet. The effect is two-fold: in the first piece, 'Heavy with Sonata', we get reminded across three movements that rock music is heavily influenced by baroque music. With its continuous bass lines and the percussive note of the keyboard single-handedly, the basso continuo sets the rhythm section for the other instruments. Ricks uses this masterly, starting with single rhythmic notes whilst moving into a full-blown basso continuo in the third movement. Above this, the strings are allowed to go off, creating at the same time a grounded and free music atmosphere. Just as in many 'prog' and 'experimental' rock pieces, though you should not take the comparison too literally, we are NOT listening to rock music here!

The guitar takes over the harpsichord part on track four, 'Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri (1683–1727). The baroque feeling remains, although the music could hardly be further away, not only on the timeline, a really weird but also beautiful experience reminding of Palestrina (or Pilestri, who may have not even existed) just as well as Bartok, Berg, Janacek or Fluke-Mogul. The 'Piece for Mixed Quartet' returns to the harpsichord and a game with setting melodic elements in contrast with 'free improvisation' passages. An 'assemblage' as the CD title and title of the second movement declare. This works exceptionally well: just enough baroque to ground you and plenty of dissonances to remind you that you live in the 21st century.

The final 'Assemblage Chamber' is an electronic piece in which Ricks has gathered fragments of previous pieces into ... an assemblage. We hear baroque orchestras through the haze and across a city square through the urban noisescape. Single notes ping up and down over the backdrop, gradually developing into something more coherent and layered, until the piano and harpsichord provide a brace again, holding the piece together. A masterpiece in contrasting and integrating musical elements whilst not forgetting that they still have to constitute a 'musical piece' with structure and

tension.

— Robert Steinberger, 5.31.2022

http://shipwrecklibrary.com/the-modern-word/interview-steven-ricks/

— Allen Ruch, 2.15.2022

The four Steven Ricks works on another New Focus Recordings CD are also blends of influences, although Ricks seeks to engage an audience by incorporating references to Baroque music – and some actual Baroque music – into pieces that in several cases include harpsichord. But make no mistake: this is very decidedly contemporary avant-garde material, from its odd titles of pieces and movements to its use of electronics as well as acoustic elements. Heavy with Sonata, which opens the disc, is for violin (Aubrey Woods), viola (Alex Woods), and harpsichord (Jason Hardink), and actually starts its first movement with the rhythm of a French overture, played on the harpsichord. But the harmony, instrumental combinations and techniques, and overall approach are very decidedly contemporary, as are the movement titles: “Plotting Our Next (Dance) Move,” “Sarah’s Gigabit Broadband,” and “I’ll Amend the Current Trend.” Actually, at least on one level, this is all pretty silly, subverting the sort-of-Baroque elements and the harpsichord sound itself by inviting listeners to hear material that was never used or intended to be used in this way. But of course that is often the point of some composers today: to take the past and stretch it beyond recognizability while supposedly paying homage to it. Ricks actually takes this even further in Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri (1683-1727), managing to incorporate a quotation from Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons into a work filled with thoroughly modern pops and plucks and snaps and unusual instrumental juxtapositions: it is written for guitar and prepared guitar (Daniel Lippel), violin (Miranda Cuckson), viola (Jessica Meyer), cello (Caleb van der Swaagh), and bass clarinet (Benjamin Fingland). Actually, a number of elements of this piece are fun to hear simply as sound-world snippets, but at more than 14 minutes, the work – the longest on the disc – just does not sustain. Harpsichord is again part of the ensemble in Piece for Mixed Quartet, and again played by Hardink; the two-movement composition also includes violins (Gerald Elias and Hasse Borup) and cello (Walter Haman). This is a piece that never actually goes anywhere: this-and-that contrast with that-and-this, and there is even a tiny passage that genuinely sounds Baroque, but the main point here is setting the instruments in conflict with each other. The disc ends with an extended work for electronics, performed by Ricks himself, that is called Assemblage Chamber. It incorporates snippets of the snippets of material from other works on the CD, mixing them in the usual electronic way that so many contemporary composers favor. The main conclusion seems to be that the whole, as assembled in this piece, is less than the sum of its parts.

The atypical composer Steven Ricks brings us 3 chamber works that are put through his glitchy, collage focused formula, where Baroque templates are met with an electronic and improvisational vision.

Heavy With Sonata opens the listen with flowing strings from Aubrey Woods’ violin, Alex Woods’ viola and Jason Richards’ harpsichord, where tension and beauty meet with detailed attention to rhythm and a distinct harmonic language that is quite unpredictable and exciting.

Reconstructing The Lost Improvisations Of Aldo Pilestri follows, and presents very dynamic string work thanks to Miranda Cuckson (violin), Jessica Meyer (viola) and Caleb van der Swaagh (cello), as Daniel Lippel’s guitar and Benjamin Fingland’s bass clarinet help cultivate an improvised landscape of Baroque influences, meticulous pitch manipulation and unusual rhythms.

The back half presents Jason Hardink’s dreamy harpsichord alongside violin, viola and cello from Gerald Elias, Hasse Borup and Walter Haman, where soloistic gestures and off kilter repetition is turned into a refined science, and Ricks’ electronics populate the 12+ minutes of Assemblage Chamber, where a strategic minimalism is executed with keen attention to aesthetics and sci-fi friendly bouts that are quite meditative, too.

A very innovative and ambitious affair, Ricks assembles contemporary chamber sounds in iconoclastic ways on this superbly textured outing.

— Tom Haugen, 11.06.2022

New music that cannibalizes old music has produced some striking creations like Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia, perhaps his most popular work, particularly because of the third movement and its ongoing quotation of the Scherzo from Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony. Steven Ricks doesn’t quote any previous work in this collection of pieces titled Assemblage Chamber, but three of the four works here are very adroit and imaginative mélanges of Baroque style and Postmodernism. Ricks, who is a professor of music at Brigham Young University, is a master of sleight-of-hand, so that you can never be quite sure if you are hearing pastiche, imitation, or complete originality. We are close, however, to Alfred Schnittke’s polystylism, which worked with the same bag of musical tricks, and since I admire Schnittke’s six concerti grossi and their hallucinatory mixture of Bach and the avant-garde, I was sympathetically disposed to Ricks’s ventures from the start.

The first and most entertaining piece is Heavy with Sonata from 2021, a reimagined trio sonata for violin, cello, and harpsichord. Like Berio, Ricks leads us into a delirious swirl of harmony, color, and speed. Unlike the Baroque trio sonata, the leading voice here isn’t the violin but the harpsichord. Ostinato rhythm is sometimes used percussively in clacking repetition, sometimes in Minimalist “loops” that remain fixed while the violin and cello freely soar above. The hardest aspect of music to describe in words is instrumental color, yet this is a department where imaginative effects abound in the score’s three movements, whose playful titles point to the whimsy of Ricks’s style: “Plotting Our Next (Dance) Move,” “Sarah’s Gigabit Broadband,” and “I’ll Amend the Current Trend.”

Slightly expanded instrumentation gets us to Music for Mixed Quartet, which adds another violin to the cello and harpsichord. Instead of whimsical quasi-Baroque dance or moto perpetuo, which giddily sustains Heavy with Sonata, Ricks now tilts the mix toward Modernism through discontinuous gestures, dissonance, and only hurried glimpses of Baroque styling. The result is skillful and engaging, but Schnittke’s approach, which begins with Baroque pastiche and then continually builds in intensity as a storm of avant-garde gestures breaks out, proves more satisfying.

In the third of his Baroque mélanges, Reconstructing the Lost Improvisations of Aldo Pilestri (1683–1727)—the tortuous title is itself baroque—Ricks employs the same method of ducking in and out of genre worlds. We peek into near-quotation of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and out again, where the next gesture might be an atonal solo or a whirl of contending, entangled voices. The instrumentation this time is led by a guitar, including a prepared guitar, the rest of the ensemble being a string trio (violin, viola, cello) and bass clarinet. This piece struck me as the farthest removed from a Baroque foundation, which makes it seem free-form. But Ricks has such a good ear that he implicitly makes connections that unify the score as it unfolds.

One of Ricks’s longtime specialties is electro-acoustic music, represented here by Assemblage Chamber from 2022, for which no performers or instrumentation is provided. The piece is the one anomaly on the program, even though it gives the album its title. Electronica is rooted in the invention of soundscapes, and the one Ricks has devised, if I can trust my ears, takes off from acoustic string instruments, which are then melded into their electro version. The result is like a continuous tapestry of mostly gentle, familiar musical sounds that varies between flowing and static. Pleasant as Assemblage Chamber is, nothing happens to rival the ingenuity of the three Baroque-inspired works.

No one is likely to miss my enthusiasm for this release, which I warmly recommend. The extensive program notes, however, mix intelligible speech with obscurantism (for example, musical idioms are “conjugated and re-conjugated”), while the opening half-page offers a huffy rebuff to the mistaken idea that Baroque music was in any way “mechanical or rule-bound.” Much of it, of course, was both. Otherwise, I have only praise for the excellent performances and the vividly clear recorded sound. Huntley Dent

— Huntley Dent, 11.30.2022